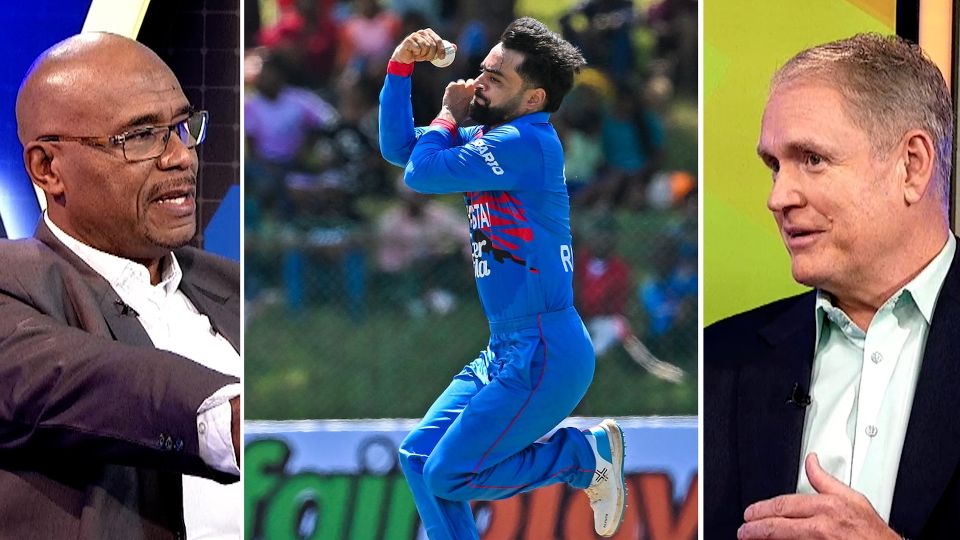

Ian Bishop and Tom Moody discuss the challenges of bowling in ODIs today

Players who seek to master ODI cricket must keep evolving constantly; the format keeps getting tinkered with so it doesn't go stale. Bowlers must adjust to two new balls that eliminate reverse swing and handicap spinners, field restrictions that encourage boundary-hitting through the middle overs, and batters emboldened by T20 cricket. Two astute observers - Ian Bishop, former West Indies fast bowler and now arguably the best researched commentator in cricket, and Tom Moody, former Australia allrounder and until recently part of various T20 dugouts - talk about the challenges and opportunities for bowlers in the format.

What's the essential difference between T20 and ODI bowling?

Ian Bishop: For me, there's still a place for Test-match-type length bowling from a fast-bowling perspective in both formats. You look at Mohammed Shami in T20 cricket and Mohammed Siraj in 2023 in T20 cricket; Josh Hazlewood's principles, certainly with the new ball and in the powerplay, in both forms of the game are still good.

That three-quarter length, even though people say it's predictable, Shami bowls it well. So from a seam-bowling perspective, there is still room in a lot of conditions. When it's flat, you have to change up and vary a little bit more. But that tight off-stump line, fourth-stump line, a little bit in, little bit out, the use of the short ball - still applies in 50-over cricket across a lot of conditions.

Tom Moody: I agree. I think it depends on what type of bowler you are. The three that you mentioned are good examples. Their skill level is good enough to be able to get the ball to move laterally, whether it be in the air or off the seam on that length you're talking about, which is in that six-to-eight-metre range [from the batter's stumps], to challenge the inside and outside edges of the bat. Particularly in 50-over cricket, where you are using two new balls, the bowlers have the advantage of a narrow window where they're going to get some assistance. Obviously that window can be a little bit wider [in some cases]. There may be some moisture in the pitch, may be a little bit more grass on the surface, overhead conditions that bowlers will welcome, and that window may expand to the first ten, if not 15, overs, where ball dominates bat.

Bishop: Shaheen Shah Afridi bowls a different length, a fuller length. Mitchell Starc, at his very best, a different length. But the common denominator is that they'll swing it at pace.

Moody: They are trying to hit you on the front pad or bowl you. And the other thing is that the majority of white-ball batters - and quite a few of them cross over to Test cricket as well - technically create an opportunity for you to go inside the bat and outside the bat, because their game is based around power. Their hands aren't aligned with their body like a traditional Test batter's would be. Their hands are a little bit further away from their body so they can engage their bottom hand to search for power and also hit through the leg side.

So does T20 batting help ODI bowlers?

Moody: In some conditions, but I think it can work the other way as well because of what we saw in the last IPL with the Impact Player rule. We've seen batting sides become a lot braver and bolder with their approach and we're seeing scores consistently over 200. I wonder whether that trend is going to carry over into 50-over cricket, where a lot of your T20 players that play 50 overs will be braver because they know there's more upside than they previously thought. The ceiling's a little bit higher than they anticipated. So if conditions aren't challenging them, they won't be as cautious, knowing that they've got 50 overs to set a platform to launch.

"The majority of white-ball batters technically create an opportunity for you to go inside the bat and outside the bat, because their game is based around power. Their hands aren't aligned with their body like a traditional Test batter's would be"

Tom Moody

"The majority of white-ball batters technically create an opportunity for you to go inside the bat and outside the bat, because their game is based around power. Their hands aren't aligned with their body like a traditional Test batter's would be"

Tom Moody

Bishop: When England decided from 2015 to 2019 that they were going to revolutionise their game, the foundation was: we'll prepare flat pitches so our guys can go hard. Jonny Bairstow, Jason Roy and those guys went very hard because the ball didn't do as much laterally and they were able to hit through the line and it took one-day batting to another level. So if the ball isn't doing anything, you're going to see that. A lot depends on pitches to keep bowlers in the game.

And to your point about impact player, what it has done is changed the mindset. Even if the impact player comes in and he hasn't been winning as many matches as you think, just knowing that an extra batter is there - guys have freed their minds up and are playing more aggressively. So even if you take away the impact player, guys now know things are possible beyond what we were playing for the last four or five years.

Moody: It's made them realise that their game can go at another level without the consequence of failure.

In the brief window in ODIs when the ball is moving for five to ten overs, is there a case for bowlers to err on the side of aggression?

Bishop: If we go back to Brendon McCullum's captaincy in a World Cup game in 2015, for example, where he started with three slips and a gully against England, I know a couple of West Indian captains have made the effort to have more attacking bowlers than defensive types while using the new ball - trying to get bowlers who swing it or guys who move it off the seam because you're looking for wickets up front.

Attacking is a big part but attacking right through the innings because of the nature of four fielders outside the circle during overs 11 to 40 - the theory is that if they get in, good batters will be able to accelerate anyway. So you want to get batters out rather than try just to limit them a lot of the time.

Moody: I'd agree with that. It depends on the conditions but in my view you should always be looking for wickets regardless of the phase. You should have the artillery in your attack to be able to take those wickets, whether that's high pace, quality swing and seam or mystery spin. You might find the surface is pretty benign and the best option is to open the bowling with a Sunil Narine to take wickets so you can expose their middle order as soon as possible.

What we've seen in 50-over cricket recently is that a lot of teams tend to stack their batting with a lot of real impact players right down at six and seven. So you see [Glenn] Maxwell and [Liam] Livingstone, for example, bat six and seven. One of your real threats is not coming in until potentially the last 15 overs, so you want to expose them early.

What fields do you set in the middle overs in ODIs when trying to get wickets?

Bishop: When you say "take wickets", how do you take wickets?

For example, we know with a wristspinner, it's each way deviation, so you just can't hit through the line; through the gate, outside edge for a fast bowler. Kind of similar in that movement-away movement-in or bouncers hitting a different part of the bat. But I just think it's a nuance, right? Because I'm looking for wickets, how am I getting wickets? It could be by having a slip and a gully; having a man on the hook for the short ball. If a batsman comes in playing a lot of shots, I could bowl a defensive length but still be looking to get a wicket because I know he's looking to play some shots and if he's looking to hit my length ball off the top of the bat, it will go to the deep fielders. Or you can bowl an attacking length, which is a lot fuller, and look for swing.

Moody: But that attacking length - you'll know within three balls whether it's worthwhile maintaining that length because if it's not swinging, it's swinging through the covers for four.

Bishop: It could, but if I'm 6ft 6in or 6ft 7in, a Curtly Ambrose or Josh Hazlewood, and I know someone's trying to hit me off my length and we are bowling what we call a hard length - the splice of the bat [will send the ball] up in the air. So my mindset is that I can get wickets by using attacking length and sometimes maybe less so by bowling a defensive length and luring him into a mistake because he's looking to attack.

Moody: I think that's a philosophy for a lot of bowlers in T20 cricket and on the flatter wickets. They come off second-best because I think batters have become braver and have developed shots we haven't seen before. So that length ball you are talking about, there's no reason why Kane Williamson or Joe Root, who may not be your quintessential sort of attackers in that top order, can't get inside it and scoop it over short fine leg. You've got deep square back because you want to use that short ball as an option. So that's the challenge if there's no movement.

I still recall a conversation I had with Glenn McGrath. The question was: what do you do if someone's hitting you off that length? McGrath's length is the length we're talking about - that six-to-seven-metre length coming from 6ft 6in, steep bounce into the top half of the bat. Glenn's answer was: "I hit that length even harder." So if I maintain perseverance on that hard length, I know with the extra bounce I get, if I'm hitting the seam, the little bit of movement I may get into the batsman or away from the batsman is enough to cause an error.

"Attacking is a big part but attacking right through the innings because the theory is that if they get in, good batters will be able to accelerate anyway. So you want to get batters out rather than try just to limit them a lot of the time"

Ian Bishop

"Attacking is a big part but attacking right through the innings because the theory is that if they get in, good batters will be able to accelerate anyway. So you want to get batters out rather than try just to limit them a lot of the time"

Ian Bishop

He may hit me for two sixes, that's fine. But 1 for 12 is a good result off three balls. That was McGrath's philosophy. Why change my sweet spot to walk into where you want me to walk into and then try to bowl a yorker, which then gets clipped through the leg side for four, or bowl a bouncer out of frustration, which gets a top edge for six or hit cleanly over midwicket for four or six? I think that was pretty much his philosophy in Test cricket as well. It was like, "I'm just going to be horribly disciplined on a dinner plate on a length and make it very difficult for you."

What are you doing with the field placings then?

Moody: The captaincy is really important in this situation because if you are looking for wickets and you are looking at using your resources in different ways depending on how your squad is structured, you need to be creative. We talked about McCullum with the three slips. If you're bowling a mystery spinner, there's nothing wrong with putting a silly point in there. And even if it's just there for the presence, for two or three balls, it's creating a point of difference. You're creating an illusion that there is something happening there, and there is a bit of pressure around. It may be the flattest wicket in the world, but you are creating an illusion that we've got control of the situation here.

Or I've got a leg slip. "Why has he got a leg slip in?" "Is he bowling a straight line?" "Is it turning and bouncing?" "Is that going to come into play?"

All those little subtle things that good captains do, even though there may not be a clear method or strategy or historical sort of record of a player hitting the ball in the air through straight midwicket. Why have you got a catching straight midwicket? Well, it's there to sow a seed of uncertainty. You've got a fast bowler bowling, you have two fielders back on the hook. You may subtly move one 15 metres behind square and bring your fine leg a little bit finer. You're not doing anything different but you are just making a subtle adjustment to your field, which is sowing a seed of doubt in the player on strike.

Bishop: A lot of bowlers are starting with a deep square leg and a deep point. With that deep point, I know a lot of people question it, but guys aren't necessarily looking to run the ball down. They're looking to punch the ball hard. So some guys will see a deep point and feel they need to open the face a little bit more, which brings an edge into play. Or think they need to close the face a little bit and play a little bit squarer, which allows for deviation.

Moody: It's an interesting point you make about the deep cover-point fielder that's taken over in a lot of cases from the traditional deep third. My theory around that is more to do with the pace of the game and how hard players are going at the ball. Generally, when the ball is flying behind the wicket, the way players are playing, particularly in those powerplay overs, the ball's more than likely going to fly squarer because of the bats they use and the surfaces they play on. The deep third is the old "run it to third for one" to get off strike. It's outdated now. Guys are hitting the ball in front of themselves, therefore the ball is travelling to point and behind point instead of behind the wicket.

With power-hitters like Liam Livingstone, death overs in ODIs can possibly extend up to 30 overs

R Satish Babu / © AFP/Getty Images

In T20s, I think the bowlers are trying to get the batters to hit to the deep fielders. It's a good ball if you get hit straight to a deep fielder. In ODIs, though, you can do more with the infielders, right? What are you looking to do with your fields in the middle overs if you are looking for wickets?

Moody: A lot depends on the bowlers you have at your disposal. If you've got [legspinners like] Wanindu Hasaranga, Rashid Khan or Adam Zampa, you've got an opportunity in any phase to take wickets. But if you are bowling in that phase with a traditional offspinner, quite often you see that offspinner occupying a defensive role, having four fielders out on the leg side, bowling into the right-hander's hip and being satisfied at getting through an over without being hit for a boundary. He's not even attempting to take wickets. He's really turning over overs during a challenging phase.

The other thing we see work successfully - and it's not every country that has these bowlers at their disposal - is those who can bowl 150kph. Lockie Ferguson successfully did it in the 2019 World Cup in that middle phase for New Zealand. I think that's going to become more and more on trend because, no matter how good a player you are, everyone is challenged in some way, mentally or technically, against high pace. I think your enforcers and your mystery spinners or classical legbreak bowler who has a very good wrong'un will be your best bowlers in that phase. They give you your best chances of taking wickets because you've either got batsmen that are not reading spin and trying to maintain a healthy run rate or you are challenging the batter with the unpredictability of the fear of high pace.

Bishop: I don't think we can cover all the tactics for different teams in this discussion, but about the high-pace enforcer - because you've only got four fielders outside the circle, you'll find that most times there's going to be a deep third, fine leg, a deep square and a deep point, which means you're taking a risk if you pitch the ball up unless there's significant movement. So those enforcers come in handy because they will be bowling into the pitch and it's hard to score off them down the ground unless it's really flat. Batsmen have to score off square and that's where your fielders are - square, behind square.

So you can't afford more than one fingerspinner in your side? And even that one has to also contribute with the bat.

Moody: It depends on the quality of the fingerspin. We see a lot of batsmen at Nos. 5, 6 and 7 that bowl fingerspin and are handy to have in your side because they give you a little bit of depth and an option for match-ups. But I still think there's a place for your specialist fingerspinner, because they're crafty enough, clever enough through the air to create enough deception to create opportunities.

"The mental side of bowling at the death is hugely underappreciated. When you are vulnerable and you've got huge pressure on you, it becomes a game of how can I block out this noise and get back to the most important thing: the execution of what I can bowl"

Tom Moody

"The mental side of bowling at the death is hugely underappreciated. When you are vulnerable and you've got huge pressure on you, it becomes a game of how can I block out this noise and get back to the most important thing: the execution of what I can bowl"

Tom Moody

Bishop: Shakib [Al Hasan].

Moody: Shakib, but he obviously bats as well. I still think the very best spinners are always going to present a challenge. They don't have to turn it both ways, but they are few and far between because most teams are promoting and always in search of someone that spins it both sides of the bat, whether it's out of the front of the hand or the back of the hand.

Bishop: Oh, there's a few guys. Shakib walks into that Bangladesh team as a bowler or a batter and he has other guys around him as well. Akeal Hosein is another one, more in T20 than 50 overs, but his 50-over game is getting better. Guys who can attack the stumps and just turn the odd one. I do think there's a match-up.

Moody: [Mitchell] Santner can bat as well, but you know he's going to bowl his ten overs very effectively during the first two phases of the game.

Bishop: Axar Patel, in the right conditions, is a handy guy. Can bat as well.

Talking about players like Livingstone and Maxwell - power-packed hitters at six or seven. They are also looking to maximise overs 30 to 40 before the extra fielder goes back. So is that almost like a 20-over death phase now in ODIs?

Moody: There's great depth to that answer because it could be more than 20 overs. It could be 30 overs, depending on the conditions you're playing in. You might recognise that it is very much in favour of the bat, there's very little movement for your fast bowlers with swing, there's very little pace in the wicket. So suddenly your high-pace options are nullified on a docile surface. Suddenly you are reaching totals of 400. Particularly in India, there'll be certain grounds where that's very achievable if you've got the batting depth and the power down the order for that sort of fearless approach.

Bishop: That's why with those restrictions and these sorts of pitches, you're seeing in some countries and some grounds that 300 is only par. You have to start aiming for 350 because you've got guys like Heinrich Klaasen who specifically challenge oppositions in the middle overs when you expect spin to be bowled. Then somebody else will pick up the slack in overs 30 to 40 or 40 to 50. So I think it's very strategically based and has many layers to it.

Moody: "In my view you should always be looking for wickets regardless of the phase. You should have the artillery in your attack to be able to take those wickets, whether that's high pace, quality swing and seam or mystery spin"

© BCCI

Is death bowling in ODIs any different to T20s?

Moody: No, the approach is actually identical. It's the execution in both that is the most critical component to it. And there's two parts to the execution. There's the skill element, the ability to consistently bowl yorkers at the crease, because that is still the best ball, a defensive ball, unless you're playing on a slow wicket, where your offcutter is staying in the wicket and ballooning up and nearly impossible to hit. But we're assuming it's good batting conditions.

The second part is the mental side. The mental side of bowling at the death is hugely underappreciated, because that is the hardest thing. If you are mentally on top of your game, your execution and the reliability of that execution is seamless. But when you are vulnerable and you've got huge pressure on you, whether it be through external noise, internal noise, whether it be a captain telling you five different things, it doesn't matter how skilful you are. It becomes a game of "How can I block out this noise and get back to what's the most important thing?" And that is the execution.

Bishop: Bowl your straight yorker, wide yorker. There were some teams and some bowlers who are more comfortable bowling the hard length, bowling it into the pitch, cutting it off the surface, pace off the ball either way. Knuckleballs come into it now. So I think the principles are basically the same [in ODIs and T20s], variations are same, or if you are a specialist like [Matheesha] Pathirana or [Lasith] Malinga, use your yorker mixed up with a slower ball and the odd short ball.

Curtly Ambrose always said that when he bowled three-four overs at the end of innings, mentally it was so demanding and draining. Sometimes it was perhaps as hard as a day of Test cricket bowling because for every ball you are sharply focused, thinking of an alternate plan.

Dwayne Bravo also talks about it all the time. Sometimes if he's bowling to AB de Villiers, he has to be so on point and coming up with a new plan. Guys like Suryakumar Yadav and AB have so many shots, you're shattered at the end of it. You felt as though you've bowled 12 or 14 overs because of that same mental process. If you don't have the mental fitness to execute, you're going to make mistakes.

Can you define this mental strength?

Bishop: It's being clear in your plan, having practised whatever method and variation you want to come up with, but being very clear in that plan and not doubting yourself.

Moody: It's down to one word and that's trust. Trusting your process in what you do at that point of the game, whether it's the back end or the front end of the game. You are always under pressure, but you're under extreme pressure generally at the back end, which is what we're talking about. Just trusting what you do without wavering at all. That is mental toughness.

"Guys like Suryakumar Yadav and AB have so many shots, you're shattered at the end of it as a bowler. You feel as though you've bowled 12 or 14 overs. If you don't have the mental fitness to execute, you're going to make mistakes"

Ian Bishop

"Guys like Suryakumar Yadav and AB have so many shots, you're shattered at the end of it as a bowler. You feel as though you've bowled 12 or 14 overs. If you don't have the mental fitness to execute, you're going to make mistakes"

Ian Bishop

Bishop: If you are worrying and stressed, suddenly you get tired because your mental energy is going somewhere else.

Moody: You cannot have "what if" come into any thought process.

So what if you've nailed your yorker but it's been ramped for six. This is not a "what if". This has happened.

Moody: With any bowler, at any phase of the game, you don't judge yourself on outcome. You judge yourself on process. So if you've done everything you possibly can to execute what you are intending to do, but there is a genius at the other end that ramps you for six... it doesn't even have to be a ramp for six. We see so often great yorkers get inside-edged between the batsman's legs for four, or outside-edged past the keeper for four. That's a win from a bowler's perspective. You judge yourself on the balls you bowl in a game purely on your thought process and how you've executed that against the outcome.

Bishop: If I were to talk to a young bowler today in that phase, having misread it myself across my career, sometimes we try to over-experiment down the back there. Whatever the outcome is, I want to bowl my best ball. And if that best ball goes for runs, mentally you have to be satisfied with knowing sometimes there's not much I can do with the range of strokeplay that we have. If I'm playing at Chinnaswamy versus at the MCG, I have to expect a certain differentiation in the level of scoring. So that mental part of the game comes back. But I just want guys to not feel pressure, just bowl your best ball. You can't control the outcome.

Moody: That also goes back to how we measure success. I think particularly in white-ball cricket, the obsession with fifties, hundreds and wickets is old-fashioned, because as a coach you can go up to a bowler who has bowled ten overs and taken 1 for 70, pat him on the back and tell him he had a really good day. Even though he's probably thinking it's not ideal, what he has done has been exactly what he's been working on.

Has bowling in T20 cricket helped condition bowlers to the wild mismatch between execution and result, in the death overs particularly?

Moody: Yeah, I think they're conditioned to the extreme upside and downside the game can present. In the old traditional 50-over cricket when you had an outlier with regards to a poor performance, it really stood out, and now it's just sort of, "Yeah, this happens, onto the next one."

Glenn McGrath's response to being hit off a good length was to hit that length even harder because with the extra bounce, if he landed the ball on the seam, the movement he generated could force the batter to commit an error

Clive Mason / © Getty Images

Earlier batting second in India was a clear advantage, but of late, because of the earlier starts, we see there is a window before the dew comes in when the ball does a lot more. We have seen India take four-five early wickets and then guys like Dasun Shanaka and Michael Bracewell batting easily. Is there something to it?

Moody: If we look at pink-ball Test cricket, it's a vastly different game from when you start at 2pm to that twilight period and then the evening - that's the window you are referring to. But it's a narrow window and I'd be very surprised if teams aren't planning around that phase of the game, recognising there's a threat for 60 or 90 minutes of the game. You either structure your bowling attack around that threat or make sure you are prepared from a batting perspective to absorb pressure during this phase and then play catch up when things turn quite quickly with dew and you know you can get those extra runs.

Bishop: That feeds into whether you might bowl spin upfront because it'll be dewy later, or whether you feel the ball will seam for a little while and you get your most attacking swing bowlers and leave the guys who hit the pitch for a little bit later. It depends on the conditions, but spin is a variable as well that comes into play there.

You see these 15 overs as the phase where teams can maximise with swing bowlers. But then conversely, you are also leaving your spinners to bowl with the wet ball.

Moody: If you have that dilemma, pick the bowler that's the biggest threat. So if you have a spinner you feel is going to take early wickets ahead of one of your swing bowling options, the spinner gets the nod.

What's the ideal composition of an attack in ODIs in India?

Moody: I think ideally you need left- and right-arm swing. That's absolutely ideal. You need one high-pace bowler, minimum, someone who can bowl 145-plus, someone who can bowl wristspin, and then a fingerspinner, either left-arm orthodox or offspinner, to give a little bit of variety and depth to your attack.

Sidharth Monga is an assistant editor at ESPNcricinfo

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.