Leonidas at Thermopylae: Hanif rebuffs one at Lord's

Leonidas at Thermopylae: Hanif rebuffs one at Lord's

Letter from... Cholderton, Wiltshire

Dear Cricket Monthly,

I had never seen a first-class cricket match when Hanif Mohammad scored his famous 187 not out in the Lord's Test in 1967. However, I read everything about it in the Daily Telegraph.

I was so moved by this feat of endurance that I wrote an essay on Hanif's innings for my English class. I told the story of how this tiny figure had defied the might of the English bowling attack for hours on end, like Leonidas defending the pass at Thermopylae. Ever since, Hanif Mohammad has remained for me the symbol of courage, endurance and stoicism.

I was ten years old at the time and the 1967 series left on me the impression that Pakistani players could be heroic but that their team was not terribly good. This changed four years later with the 1971 tour. I can still feel my shock at the deeds of Zaheer Abbas in the first Test.

I was so moved by Hanif's feat of endurance that I wrote an essay on it for my English class

I was so moved by Hanif's feat of endurance that I wrote an essay on it for my English class

England had recently returned from Australia, where, thanks to the brilliant bowling of John Snow, they had secured an epic series win in the Ashes. In consequence I was looking forward to a summer of easy victories over a docile Pakistani team.

It wouldn't be quite right to say that Zaheer tore the English attack to pieces. He dismantled it with quiet efficiency in the course of his 274 runs, each one of which was painfully etched into my teenage soul. The performance was all the more shocking because he looked like a gawky student, shambling to the wicket in spectacles.

Until the 1971 tour I had classified Test teams into two categories. There were teams as good as England, or better - West Indies, Australia and South Africa (until their ejection from international cricket). And there were the teams who made up the numbers - New Zealand, India and Pakistan.

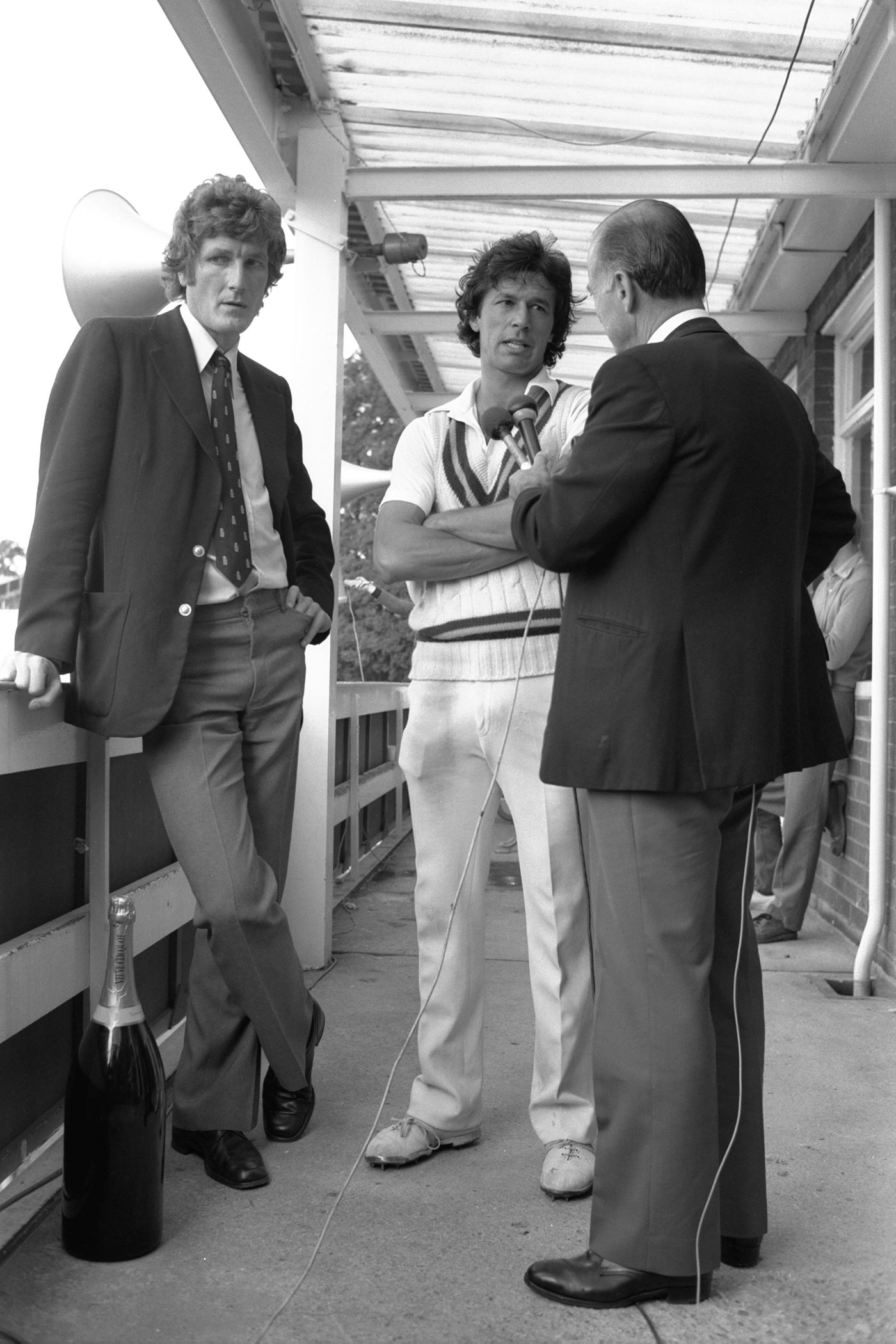

1982: Imran is interviewed by Peter West at Headingley, with England captain Bob Willis looking on

Adrian Murrell / © Getty Images

Zaheer's 274 marked the moment Pakistan moved from the second to the first category. As an England fan, I resented this very much. The half-season tour of 1974, which Pakistan went through unbeaten, confirmed that they were on the up. So did the growing number of Pakistanis in county cricket - and the stars who were later recruited by Kerry Packer.

The series of 1982, when Pakistan were led for the first time by Imran Khan, made an even deeper impression on me. By now Imran was well on his way to becoming one of the greatest players the world had ever known, and he led a team that could outplay England on their day. The 1982 series was a terrific contest and I watched with shame the decisions given by umpire David Constant during the nail-biting third Test at Headingley. I am sure that umpire Constant was not consciously biased, but some of his decisions defied belief and they all seemed to favour England.

This was a moment of awakening: I suddenly realised that there was something ugly and hypocritical about the English attitude to Pakistani cricket. As soon as they stopped being deferential losers we began to demonise them. We were all too quick to condemn Pakistan as cheats, but when an England umpire meted out unfair treatment to Pakistan he was guilty of nothing more than a mistake. I could see this double standard was a metaphor for something deeper.

We as a nation ought to have welcomed the arrival of Imran's brilliant team on the world stage. Some of us did, but too many resented it

We as a nation ought to have welcomed the arrival of Imran's brilliant team on the world stage. Some of us did, but too many resented it

In the 1980s, English cricket supporters ceased to feel well disposed towards Pakistan. They now felt fear and hostility. We as a nation ought to have welcomed the arrival of Imran's brilliant team on the world stage. Some of us did, but too many resented it. When Pakistani bowlers invented reverse swing - the greatest innovation of the modern game - we once again accused Pakistanis of cheating. Meanwhile, the behaviour of our own players was beyond belief.

I believe that the shouting match between Mike Gatting and umpire Shakoor Rana in Faisalabad was one of the lowest points in English sporting history. I do not believe that Gatting would ever have used such foul language towards an Australian or a South African umpire. Watching those horrifying pictures go round the world, it was obvious that Gatting should have been stripped of the captaincy. Instead, the tour management signalled its approval of his awful behaviour when they awarded Gatting and his team a hardship bonus.

Something went very wrong with English cricket in the 1980s. Two years after the Shakoor Rana incident, Gatting led the so-called rebel tourists to apartheid South Africa. The mentality of an English captain who could take such deep offence at an umpiring decision but turn a blind eye to the moral depravity of apartheid defies explanation.

Gatting v Rana: surely the England captain should have copped some punishment for his behaviour?

Bob Thomas / © Getty Images

Meanwhile, Imran was turning Pakistan into the greatest and most joyous cricket team in the world. In 1992, as an England fan, I was shattered by our defeat at the hands of Pakistan in the World Cup final. As someone who loved cricket and all the splendid things it stands for, I had no choice but to celebrate. Imran's team was not only better than England. Morally they belonged to another universe.

It has been very hard as a lover of cricket to follow Pakistan in the last 25 years. On the one hand, cricket still stands for all that is best and most exciting about Pakistan. On the other hand, it also expresses the corruption and the weakness of parts of the Pakistani state. The fact that some of Pakistan's greatest players have been tainted in various corruption scandals is too heartbreaking for words. This is the reason why I have come to admire the current Test captain, Misbah-ul-Haq, so much. Misbah took the reins of Pakistan cricket in one of its darkest hours, in the wake of the spot-fixing scandal in 2010.

Misbah had to confront not just corruption but also the consequences of terrorism, which, ever since the attack on the Sri Lankan cricket team in Lahore in 2009, has prevented foreign teams from visiting Pakistan and condemned its international players to foreign hotels for the majority of the year. In the face of this double catastrophe, there was every chance that Pakistan cricket could have collapsed. It took leadership of an exceptional kind for Misbah to hold the team together.

Just as Hanif glued his team's batting together at Lord's 49 years ago, so Misbah has done with Pakistan cricket itself, along with the great Younis Khan. It is an extraordinary achievement, which required discipline, sacrifice and an intense patriotism. Alongside Imran Khan and Abdul Hafeez Kardar, he can be counted as one of his country's greatest captains. I hope and believe this remarkable man will be given a hero's reception in England this summer.

Peter Oborne

Peter Oborne is political columnist of the Daily Mail, author of Wounded Tiger: A History of Cricket in Pakistan, and co-author of White on Green: Celebrating the Drama of Pakistan Cricket

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.